Ever wondered why you can feel perfectly healthy for months but still carry something as serious as tuberculosis? It’s one of the world’s most notorious diseases, a true master of disguise. TB, or pulmonary tuberculosis, hangs around quietly before unleashing its terrible side effects. In South Africa, we deal with a heavy burden of TB—the World Health Organization said that in 2023, SA reported around 360 cases per 100,000 people. But not everyone knows how cunning and complicated TB really is. Once you start to pull back the curtain on the stages of this disease, you realize TB is as much a story of the body’s resilience as it is about illness.

The Onset: Silent Arrival and Primary Infection

For most, the TB journey begins with what feels like nothing at all. The bacteria, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, slips in quietly—usually from droplets in the air when an infected person coughs or sneezes. It’s almost impossible to spot this first moment. Only one in ten people exposed to TB bacteria will ever develop active disease, because the immune system is usually primed and ready. But still, the body knows an intruder is there, and it quickly sends up defenses.

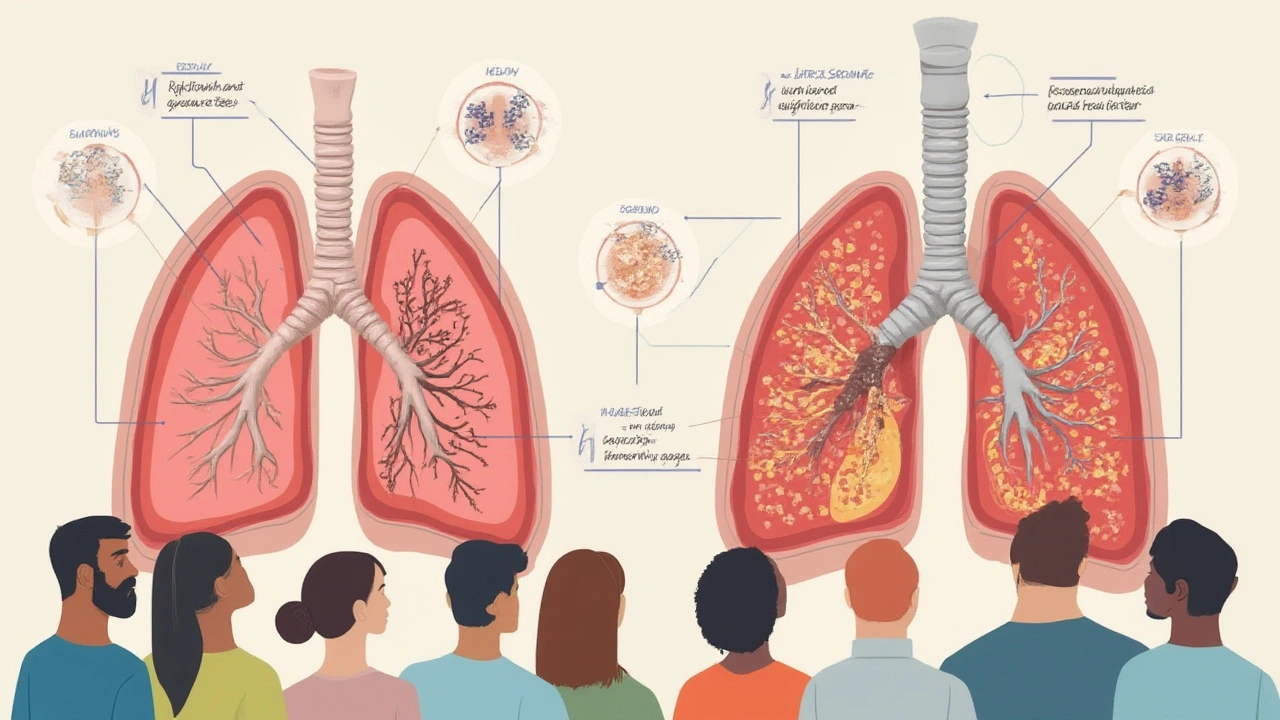

The primary stage starts with the bacteria finding a comfy spot in your lungs. The body’s immune cells gather in a sort of panicked clump, forming what’s called a Ghon focus. Sometimes this defensive group partners up with a nearby lymph node—this combo gets a clinical nickname: the Ghon complex. People at this point are usually symptom-free, and chest X-rays in healthy adults often miss it. Odd fact: among South African children, over 50% will have latent TB by age 15. The bacteria hide, wrapped in immune cells, just hoping you’ll forget they’re there.

This silent phase is called ‘latent TB.’ The germs aren’t spreading, can’t make anyone sick, and don’t cause an obvious cough or fever. You might carry latent TB for years, even decades. But don’t be fooled: a weakened immune system, diabetes, HIV infection, or even just extreme stress can wake the bacteria up. Imagine hosting a party in your lungs and forgetting the guest list—these uninvited TB germs can crash the event at any time.

During the early stage, a person’s only clue might come from a standard TB test (like the Mantoux skin test or a newer blood test). It’s common for doctors to catch TB in this phase only when screening folks who are at higher risk—healthcare workers, people who live with someone who has active TB, or those with chronic illnesses. Treating TB early is a big deal. Medicine at the latent stage (usually isoniazid for six to nine months) can prevent the drama of active TB down the road. If you’re starting to get the chills just reading about this, don’t panic—this is the quietest stage, the one with the most hidden danger, but also the easiest to stop if you act quickly.

Progression: Active Disease Unfolds

Things can get real ugly real fast once the bacteria outsmart the immune system. Only about 5-10% of people with latent TB develop active TB during their lives, but when it happens, it gets serious. The TB bacteria start multiplying, breaking out of their old hiding places, and causing all those stereotypical symptoms—prolonged cough (over three weeks), coughing up blood, weight loss, fever, night sweats, and chest pain. Sound familiar from stories or movies? They aren’t exaggerating. For millions worldwide, these signs aren’t fictional—they’re daily challenges.

South Africa is a hotspot, especially in regions like KwaZulu-Natal. Here in Durban, you can’t talk about health without talking about TB and how closely it interacts with HIV. Around 58% of TB cases in South Africa also involve HIV infection. People with weakened immune defenses—like those with HIV, young children, or the elderly—move from latent to active TB much more easily. What’s wild is that TB doesn’t always act the same way in everyone. Some folks shiver without fever, others don’t lose a gram of weight, and someone else’s only clue is a lingering cough that just won’t budge.

When TB becomes active, it can show up two ways:

- Primary Progressive TB: This type moves fast, mostly in children and people with immune weakness. Symptoms can explode over weeks.

- Post-primary (or secondary) TB: This form kicks off years after the initial infection, mostly in adults. It usually targets the upper lobes of your lungs and can form cavities where bacteria multiply by the millions. These spots are the scary ones because they spread TB like wildfire to the outside world.

If you took a chest X-ray right now of someone with active TB, you’d probably see patchy shadows or cavitations. Doctors also use sputum tests to look for the TB bacteria under a microscope. Quick facts: diagnosis is sometimes slow, which can be deadly, so rapid molecular tests like GeneXpert are now making things safer and faster in places like Durban and Soweto.

Active TB is wildly infectious—the CDC says each untreated person with active TB can infect 10–15 people a year. That’s why, if a doctor suspects TB, they won’t wait for perfect proof. They start treatment right away: usually four antibiotics taken daily for six months. Mess up the routine? The bacteria can become resistant, turning regular TB into its nightmare cousin, multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB). MDR-TB means even longer, more toxic treatment—along with a higher risk of lasting lung damage and, yes, spreading the disease.

| Stage | Estimated Cases | Typical Symptoms | Treatment Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latent TB | ~2 million | None | 6-9 months (preventive) |

| Active TB | ~248,000 | Cough, fever, weight loss | 6 months (first-line drugs) |

| MDR-TB | ~14,000 | Same + not responding to standard drugs | 9-20 months (second-line drugs) |

Easily missed fact: TB can cause silent damage beyond just breathing trouble. It scars lung tissue, causes fibrosis, and for some, breathing never goes back to normal. Folks sometimes shrug off a lingering cough or mild fatigue, chalking it up to “just a chill.” If you’re sweating through your T-shirt night after night, or if your cough has hung around past three weeks—get checked out. Fast action changes everything with TB.

Healing and Beyond: Treatment, Prevention, and Daily Life

If you’ve dealt with TB, you know treatment is a grind. Six months feels like forever, especially as symptoms start to fade after just a few weeks. That’s when people get tempted to skip doses—bad move. Stopping meds early lets leftover bacteria develop resistance. Sometimes, patients have to deal with medication side effects: nausea, mild liver irritation, orange urine (thanks, rifampicin). It’s not glamorous, but it saves lives.

Family life gets tricky too. It’s awkward having to mask up at home, open windows in winter, and cough into tissues. Community clinics in Durban have daily observed therapy sessions to help people stay on track. Public check-ins aren’t always easy—but they work. According to South Africa’s National TB Program, treatment success rates hover around 80%, which is huge compared to the dark days of the 1990s and early 2000s.

The *most important* fact: TB is treatable and curable with the right meds and support. Directly observed therapy (DOT) programs boost adherence. Treatment for MDR-TB can be daunting, taking up to 20 months and causing gnarly side effects, but access to newer meds is improving every year. TB isn’t just a medical issue—it hits hardest where poverty, malnutrition, and crowded living conditions overlap. Good food, lots of rest, and honest conversations about symptoms make a huge difference.

Vaccination—specifically with BCG (Bacille Calmette-Guerin)—offers some protection, mainly against severe childhood TB. It’s not perfect; in high-TB burden places, it doesn’t prevent all cases, especially adult pulmonary TB. But it’s better than nothing, and new TB vaccines are under trial (watch this space by 2027!).

Pulmonary tuberculosis isn’t just about coughing people in hospital beds. Its stages tell a story of silent battles, the power of prevention, and how fragile the balance between health and illness can be. Watch for symptoms, get regular TB screenings if you’re at risk, and stick to treatment if diagnosed. The stages of TB are sneaky, but with a little knowledge and courage, you can stay two steps ahead of this centuries-old disease.