When you walk into a pharmacy and find your prescription is out of stock-or worse, the price has jumped 40% in six months-you’re not just dealing with bad luck. You’re feeling the ripple of something bigger: pricing pressure and shortages in health care. These aren’t temporary hiccups. They’re structural shifts that have reshaped how medicines, equipment, and even basic care are delivered-and who can afford them.

Why Health Care Feels So Unstable Right Now

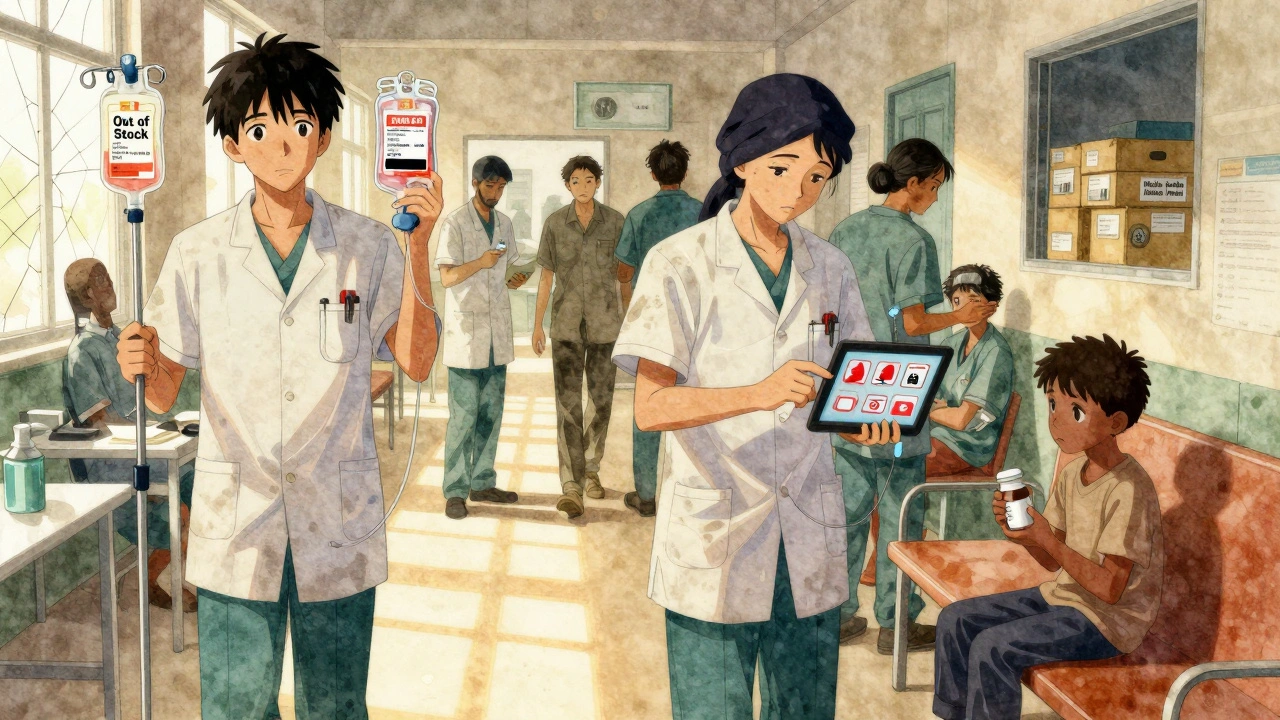

The health care system doesn’t operate in a vacuum. When global supply chains break down, it hits hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies first. During the pandemic, the world saw what happens when demand for masks, ventilators, and IV bags spiked while production slowed. But even after the worst of the crisis passed, the damage stuck. By 2023, over 30% of U.S. hospitals reported ongoing shortages of at least one critical drug, according to the American Hospital Association. In South Africa, where public clinics rely heavily on imported generics, shortages of antibiotics and insulin became routine by late 2022. What made this worse? Inelastic supply. You can’t suddenly build more factories for sterile injectables or train more pharmacists overnight. And when demand stays high-because chronic diseases don’t take a break-prices rise. The Cleveland Federal Reserve found that supply shocks raise prices nearly five times more than demand shocks. In health care, that means a single disruption in China’s chemical production can send the price of metformin, a common diabetes drug, soaring across Africa and Latin America.Who Pays the Price?

It’s not just patients. Health systems pay too. In 2021, UK NHS trusts spent 22% more on pharmaceuticals than they had in 2019, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility. Many of those increases weren’t due to inflation alone-they were because suppliers had no alternatives. When a single manufacturer controls 80% of a drug’s production, and that factory shuts down for maintenance or gets hit by a flood, there’s no backup. That’s called a single-source bottleneck. And it’s common in generic drugs. In Durban, a public clinic I spoke with in May 2024 reported that their stock of amoxicillin ran out for 11 weeks straight. The local distributor said the supplier in India had delayed shipments due to labor strikes and port congestion. Patients were sent to private pharmacies, where the same antibiotic cost R450 instead of R45. That’s a 10x price jump. For a family of four needing antibiotics for respiratory infections? That’s R1,800 out of pocket. No wonder people skip doses or go untreated.Price Controls Backfire-Here’s Why

Governments often try to fix this by capping prices. It sounds fair. But in health care, it often makes shortages worse. Take the UK’s energy price cap. In 2021, it prevented energy firms from raising prices even as gas costs tripled. Result? Twenty-seven smaller suppliers went bankrupt. The same thing happened with insulin in some U.S. states that imposed price ceilings. Manufacturers saw no profit in producing low-margin versions, so they stopped. The result? Even more scarcity. Harvard economist Martin Weitzman showed this pattern clearly: when prices are held artificially low, people panic-buy. Pharmacies run out faster. Black markets emerge. In 2022, a Reddit thread from Johannesburg described how people were trading insulin vials on WhatsApp groups because public clinics had none. That’s not access-it’s survival.

Where the Shortages Hit Hardest

Not all shortages are equal. Some hit harder because they’re harder to replace.- Injectable drugs: Antibiotics, chemotherapy agents, and anesthetics. These require sterile production. Only a handful of global facilities can make them. When one fails, the world feels it.

- Medical devices: ICU monitors, dialysis machines, and ventilators. These are complex, regulated, and take 18-24 months to manufacture. During the pandemic, many hospitals reused single-use equipment because new ones weren’t coming in.

- Raw materials: Polymers for syringes, rare metals for pacemakers, even the plastic for IV bags. All of these are tied to global petrochemical supply chains. When oil prices spike or shipping routes get blocked, the cost bleeds into every syringe.

How Some Systems Are Fighting Back

Not everyone is helpless. Some health systems are adapting. In Germany, during the peak of supply chaos, regulators temporarily relaxed competition rules so hospitals could share drug stockpiles. Within six weeks, pharmaceutical shortages dropped by 19%. That’s not magic-it’s smart coordination. In South Africa, the public health sector started partnering with local manufacturers to produce basic IV fluids and oral rehydration salts. It’s not glamorous, but it cuts dependence on imports. One Durban-based plant now supplies 30% of the province’s saline solution needs. Private hospitals are using digital tools to track inventory in real time. One network in Cape Town reduced stockouts by 28% after installing AI-driven forecasting software. They now know, weeks in advance, which drugs are likely to run out-and can reorder before it’s too late.

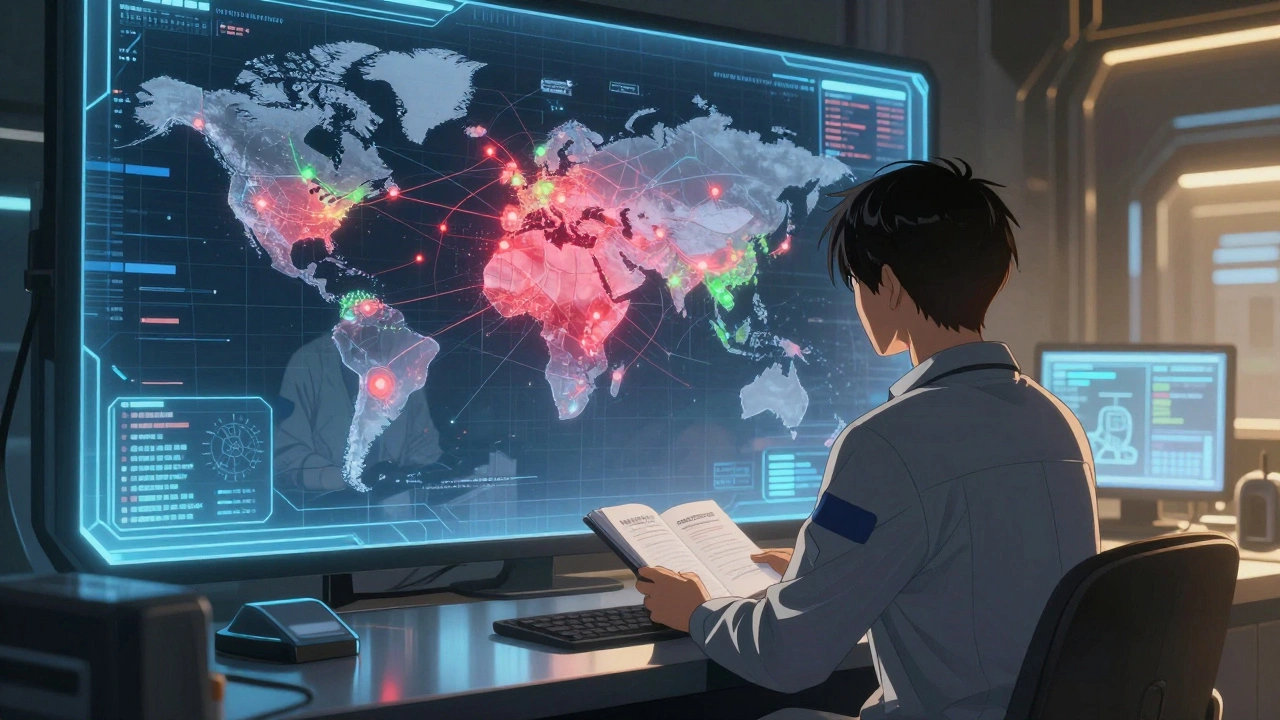

The Bigger Picture: Globalization Isn’t Going Away

You might think the answer is to make everything locally. But that’s not realistic. Most drugs and devices need specialized labs, certifications, and scale. Building a new sterile manufacturing plant in South Africa costs over $200 million. No public health budget can afford that alone. The real solution? Diversification. Companies that rely on just one supplier saw 40% more disruption days during 2021-2022, according to McKinsey. Those with three or more suppliers recovered faster. The same applies to countries. Relying on India for 80% of your generic drugs? That’s risky. Relying on China for 70% of your medical devices? Also risky. The answer isn’t isolation-it’s balance. Strategic reserves. Regional production hubs. Shared logistics networks. The International Monetary Fund warns that supply chain pressures will stay 15-20% above pre-pandemic levels through 2025. Climate shocks, geopolitical tensions, and aging infrastructure won’t vanish. So health systems need to plan for disruption-not just react to it.What You Can Do-As a Patient, Provider, or Advocate

You don’t need to be a policymaker to make a difference.- If you’re a patient: Don’t wait until your prescription runs out. Ask your pharmacist about alternatives. Ask if there’s a generic version. Keep a small emergency supply if your medication is critical.

- If you’re a provider: Track your inventory closely. Don’t assume suppliers will deliver on time. Build relationships with multiple vendors. Push for transparency in pricing.

- If you’re an advocate: Demand public data on drug shortages. Push for local production incentives. Support policies that fund regional medical manufacturing-not just emergency imports.

What’s Next?

By 2025, 60% of global health care companies plan to use digital twin technology-virtual simulations of their supply chains-to predict and prevent disruptions. That’s progress. But technology alone won’t fix this. It needs policy, investment, and public pressure. The next time you hear about a drug shortage or a price hike, don’t shrug. Ask: Who made this? Where is it made? Who controls the supply? And most importantly-what are we doing to make sure it doesn’t happen again?Why are drug prices rising even when the economy is slowing down?

Because health care demand doesn’t follow economic cycles. People still need insulin, antibiotics, and heart meds whether the economy is booming or not. When supply chains are disrupted-say, due to a factory fire in India or a port strike in Rotterdam-the supply shrinks, but demand stays flat. That imbalance drives prices up. Even if consumer spending drops elsewhere, health care spending often rises during shortages because there’s no alternative.

Are generic drugs more likely to be in short supply than brand-name drugs?

Yes. Generic drugs are often made by just one or two manufacturers because profit margins are thin. Companies don’t invest in backup factories or spare capacity. When that single plant has an issue-power outage, inspection failure, labor strike-the entire market feels it. Brand-name drugs usually have multiple suppliers and higher margins, so companies can afford to keep extra stock. That’s why you’ll see shortages of metformin or amoxicillin but rarely of insulin glargine or Humira.

Can price controls help reduce the cost of medicines during shortages?

They can make shortages worse. Price controls stop manufacturers from raising prices to cover higher costs-like shipping, energy, or raw materials. If they can’t pass on those costs, they stop producing the drug entirely. In the UK in 2021, price caps on energy led to 27 suppliers going out of business. The same happened with insulin in some U.S. states. When prices are locked low, production drops. The result? No medicine at all.

Why do some countries have fewer drug shortages than others?

Countries with diversified supply chains and domestic manufacturing capacity handle shortages better. Germany, for example, keeps strategic reserves of critical drugs and allows hospitals to share stock during crises. South Korea and Brazil have invested in local generic drug production. Meanwhile, countries that rely heavily on imports from one region-like many in Africa and Latin America-face bigger disruptions when global logistics fail. It’s not about wealth-it’s about resilience.

Is nearshoring (moving production closer to home) a good solution?

It helps, but it’s not a cure-all. Moving production from China to Mexico or Eastern Europe reduces shipping delays and political risks. But building new facilities takes years and billions of dollars. It also doesn’t solve the problem of raw material shortages-if the chemicals still come from India, you’re still vulnerable. Nearshoring reduces one risk, but you still need multiple suppliers, inventory buffers, and real-time tracking to truly protect against shortages.

Health care shouldn’t be a gamble. But right now, it often is. The next time you hear about a drug shortage, remember-it’s not an accident. It’s a system failure. And fixing it requires more than good intentions. It requires smart policy, local investment, and global cooperation.