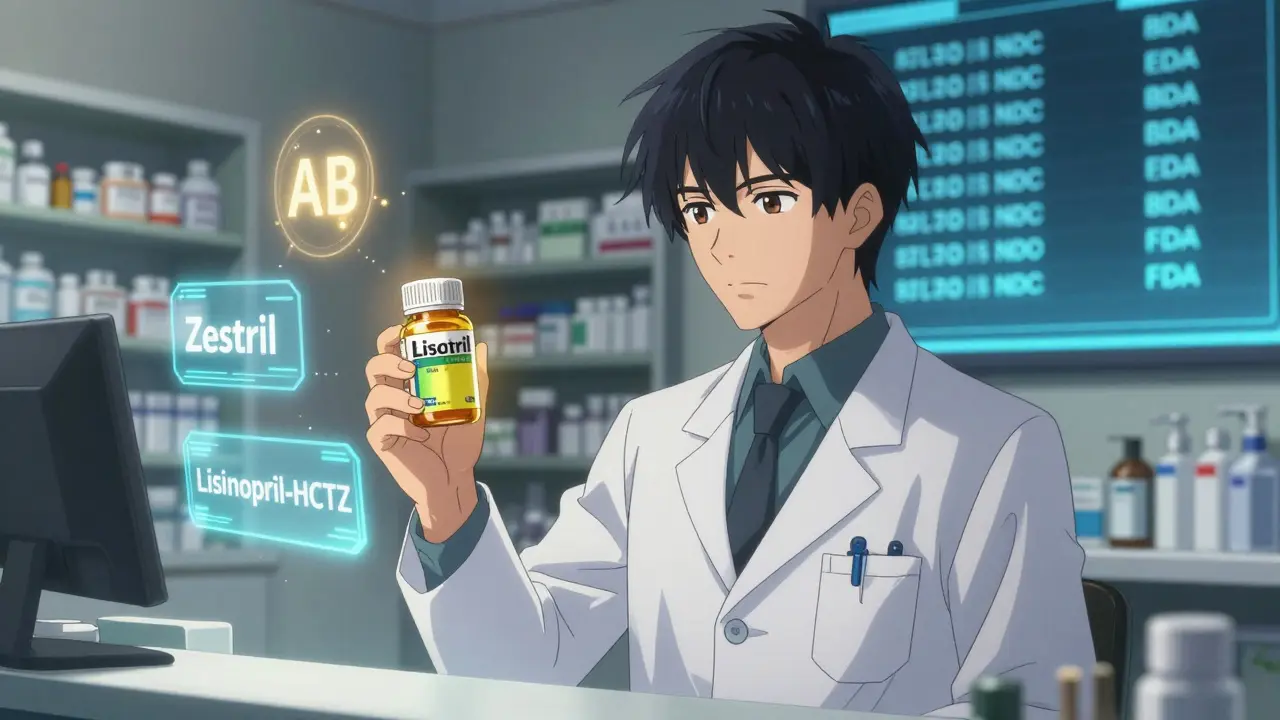

When a pharmacist pulls a prescription off the system, they don’t just see "lisinopril." They see lisinopril, Lisinopril-HCTZ, Zestril, and maybe even Prinivil-all different names for the same active ingredient. But are they the same drug? And more importantly, can the system tell the difference? In today’s pharmacy workflows, correctly identifying generic versus brand medications isn’t just about saving money-it’s about safety, compliance, and trust.

Why It Matters: Safety Over Savings

Generic drugs aren’t cheaper because they’re weaker. They’re cheaper because they don’t need to repeat expensive clinical trials. The FDA requires them to match brand-name drugs in strength, dosage, safety, and performance. But here’s the catch: not all systems are built to show that clearly.

Imagine a patient on warfarin. A tiny change in blood levels can cause a stroke or dangerous bleeding. If a pharmacy system automatically substitutes a generic without flagging it as a narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drug, the risk goes up. Systems like Epic and Cerner now include special alerts for drugs like phenytoin, levothyroxine, and cyclosporine-but only if they’re properly configured. Many smaller pharmacies still miss this step.

According to the Institute for Safe Medication Practices, over 140 adverse events between 2019 and 2021 were linked to incorrect generic substitutions for NTI drugs. That’s not a glitch. That’s a system failure.

The Backbone of Identification: NDC and TE Codes

Every pill, capsule, or injection in the U.S. has a National Drug Code (NDC)-a unique 10- or 11-digit number. It’s like a barcode for medicine. But here’s what most people don’t know: the same drug can have multiple NDCs. One for the brand, another for the generic, and sometimes even one for the authorized generic (the exact same pill, just sold under a different name).

The real magic happens with the Therapeutic Equivalence (TE) code. This two-letter code from the FDA’s Orange Book tells you if a generic is interchangeable. An "AB" rating means it’s bioequivalent and can be substituted. An "BX" means it’s not recommended for substitution. Pharmacy systems should use this code to auto-flag which drugs can be swapped and which ones shouldn’t.

But here’s the problem: many systems still rely on outdated NDC directories. The FDA updates its NDC database over 3,500 times a month. If your system isn’t syncing with the latest version, you’re working with outdated data. A pharmacy in South Carolina might see a new generic as "unavailable," while one in California already has it in stock.

Authorized Generics and Branded Generics: The Hidden Confusion

Not all generics are created equal-and not all are labeled as such.

An authorized generic is the brand drug made by the same company but sold under a generic label. For example, the brand-name Adderall and its authorized generic are chemically identical. But if your system doesn’t distinguish them, pharmacists can’t explain to patients why one costs $10 and the other costs $40.

Then there are branded generics. These are generics that got an ANDA approval but were given a fancy name to stand out. Think of birth control pills like Sprintec, Tri-Sprintec, and their generic equivalents. They all contain the same hormones, but the packaging, pill color, and brand name make them look different. Pharmacists report that 78% of patients get confused by this, especially when switching between pharmacies.

Without clear labeling in the system, pharmacists are left guessing. And when they guess wrong, patients get the wrong pill-or worse, the same pill with a different name and a higher price tag.

How Systems Should Work: Defaults, Alerts, and Overrides

Best practice? Default to generic. Not because you want to save money-but because it’s safe, effective, and often the standard of care.

Kaiser Permanente’s system does this right. When a doctor prescribes "Lipitor," the system automatically suggests the generic atorvastatin. The prescriber can override it, but only if they type in a reason. That simple step cut brand continuation requests by 37% in just one year.

Here’s what a solid system needs:

- Default to generic names in order entry and dispensing screens

- Auto-flag NTI drugs with pop-up warnings and require manual confirmation

- Display TE codes clearly next to drug names

- Identify authorized generics with a special tag (e.g., "Same as brand")

- Link to the FDA Orange Book API for real-time updates

Pharmacies using these practices report 90%+ generic dispensing rates-without a rise in complaints. That’s not luck. That’s design.

State Laws Make It Messy

Even with perfect systems, pharmacists are still stuck in a patchwork of state laws.

In Texas, a pharmacist can substitute a generic without telling the patient or doctor. In California, they must document why they didn’t substitute. In New York, they have to offer a written explanation if the patient asks. And in some states, you can’t substitute at all for certain drugs.

Most pharmacy systems don’t auto-adjust for state rules. That means a pharmacist in Florida has to manually check a dropdown menu every time they fill a script. It’s slow. It’s error-prone. And it leads to compliance violations.

The fix? Systems need location-based rule engines that auto-apply state substitution laws based on the pharmacy’s ZIP code. That’s not optional anymore. Medicare Part D requires 99.5% accuracy in substitution tracking-and auditors are watching.

Patient Education: The Missing Piece

Here’s the hardest truth: even if the system works perfectly, patients still don’t understand.

A Consumer Reports survey found that 68% of patients didn’t know generics had the same active ingredients as brand drugs. When they got a different-looking pill, they thought they’d been given the wrong medication. Some refused to take it. Others went to the ER.

Pharmacies that include a simple visual aid at pickup-like a side-by-side image of the brand and generic with the label "Same Medicine, Lower Price"-see 89% patient satisfaction. Those that don’t? Only 63%.

It’s not about convincing people. It’s about showing them. A QR code on the bag that links to a 60-second video explaining bioequivalence? That’s low-effort, high-impact.

What’s Next: AI, Genetics, and Real-Time Data

The future of pharmacy identification isn’t just about flags and codes-it’s about prediction.

New AI tools are being trained to spot patterns. If a patient has had three different generic versions of levothyroxine in six months and their TSH levels keep fluctuating, the system can flag it: "Possible sensitivity to formulation changes. Consider brand or consistent generic."

And it’s not just about drugs. The FDA’s Precision Medicine Initiative is exploring whether genetic markers can predict which patients respond better to certain brand formulations. Imagine a system that says: "Based on your CYP2D6 genotype, this brand version of metoprolol is more predictable for you."

These aren’t sci-fi ideas. They’re already in pilot programs at major health systems.

What You Can Do Today

You don’t need a $500,000 system to get this right. Start here:

- Check your NDC database. Is it synced to the FDA’s latest update? If not, fix it.

- Turn on TE code display. Make sure "AB" and "BX" are visible on every drug screen.

- Set defaults to generic names. Make brand names require a manual override.

- Train your staff on authorized vs. branded generics. Use real examples from your pharmacy.

- Create a one-pager for patients. Print it. Hand it out. Don’t wait for them to ask.

Small steps. Big impact.

Final Thought: It’s Not About Brand Loyalty. It’s About Trust.

Patients don’t care if the pill is blue or white. They care if it works. They care if they’re being treated fairly. And they care if the pharmacist knows what they’re giving them.

When your system correctly identifies a generic-and explains it clearly-you’re not just filling a prescription. You’re building trust. And in pharmacy, that’s the most important medicine of all.